Collectorsof small southern Persian tribal weavingsfor almost two decades, the authorsbecame curiousabout the nomadsof thisregion and how their woven itemswere used. Illustrationsin ethnographicliterature often provided enlightenmentand soon theywere searching for photographs of Persian nomadiclife with almost asmuch enthusiasm astheir weavings. In the first of two articles, theyfocuson the life ofthe nomadsand their use ofsmallformatweavings.

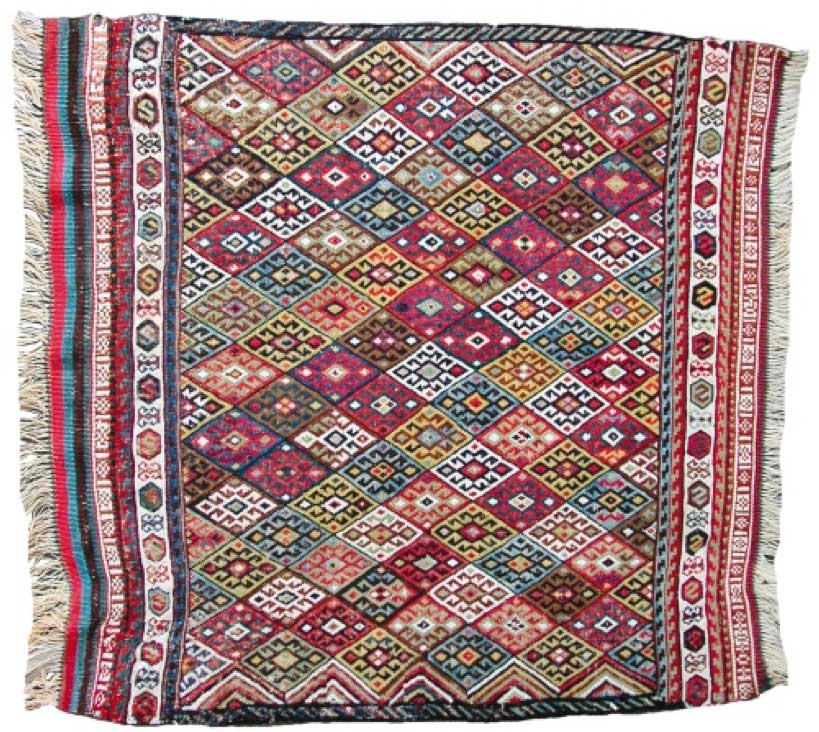

It was surprising to us how similar the lifestyles were of the various south/southwest Persian tribes: perhaps it is because the land best supports a nomadic life of sheep herding. Despite differences in language and ethnicity, each group has very similar rites and celebrations, which may be due to a common religion – Shiite Islam – some intermarriage between tribes, and shifting political alliances in difficult times. The use of weavings is very similar amongall south Persian tribal groups, so we will not distinguish between particular tribes. The field photographs in this article date from 1924 to the end of the 20th century. 1 Since most ethnographic work in southern Persia was done in the third quarter of the 20th century, 2 our discussion of nomadic life is limited to this period. Ethnographic studies and photographs exist for all the region’s major tribal weaving groups except the Afshar. The most common nomadic bags are chantehand khorjin. A chanteh is a small special purpose single bag (33, 55,, 2211). The face may be flatwoven or piled. The khorjin, or saddlebag, is the hardest working weaving of nomadic life. A complete saddlebag (1122) has two identical opposing bags with a contiguous back. Usually closed using a slit-and-loop system, their fronts, or faces, may be flatwoven, piled, or in mixed techniques. Most of the khorjin shown here are ‘fragments’, single piled faces (22, 1111). Woven in the 19th century, they are artistic interpretations of utilitarian saddlebags. Many south Persian tribal groups weave – the Afshar, Khamseh Confederacy, Qashqa’i, Bakhtiari, and Lurs are all known as fine weavers.

The nomads in these tribes are pastoralists, raising sheep and goats, migrating twice a year between their summer and winter pastures, and weaving bags and other items from sheep’s wool. Traditional southern Persian nomadic life is defined by their flocks and weavings: they are a family’s wealth, status, and livelihood. There is a rhythm to the seasons in this life. For five months the nomads live in their winter pastures (garmsir)in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. In early April the spring migration begins to their summer pastures (sardsir), which are above 6,000 feet in the mountain meadows. They live there for three to four months, and in early September the fall migration begins back to their winter pastures. Fredrik Barth, an ethnographer who lived among the Khamseh, has suggested that the migration is the grand ritual of south Persian nomadic life. 4 It is hard to disagree with him. Nomadic life is certainly defined by this twice-yearly event. For example, in the early 20th century a quarter of a million Qashqa’i migrated with all their household goods and several million animals over several hundred miles. Its enormity is difficult to grasp. In an epic photograph by David Duncan, the Qashqa’i migration looks like a military offensive.

Indeed, the planning and work that precedes each migration rivals a military campaign. Fifteen to twenty families, whose adult males are all related, live closely together in the pastures sharing work, socialising, and migrating together.

Afshar pile chanteh, late 19th century. Harmonious use of color and design, with rows of weft-substitution work on the face and back, 0.38m x 0.29m (1’3″ x 11.5″). Authors’ collection

Khamseh Confederation spindlebag face, late 19th century. The loosely woven extra weftwrapping is similar to Luri work. Wool, cotton, and goat hair are used throughout, 0.33 x 0.48m (1’1″ x 1’7″). Authors’ collection

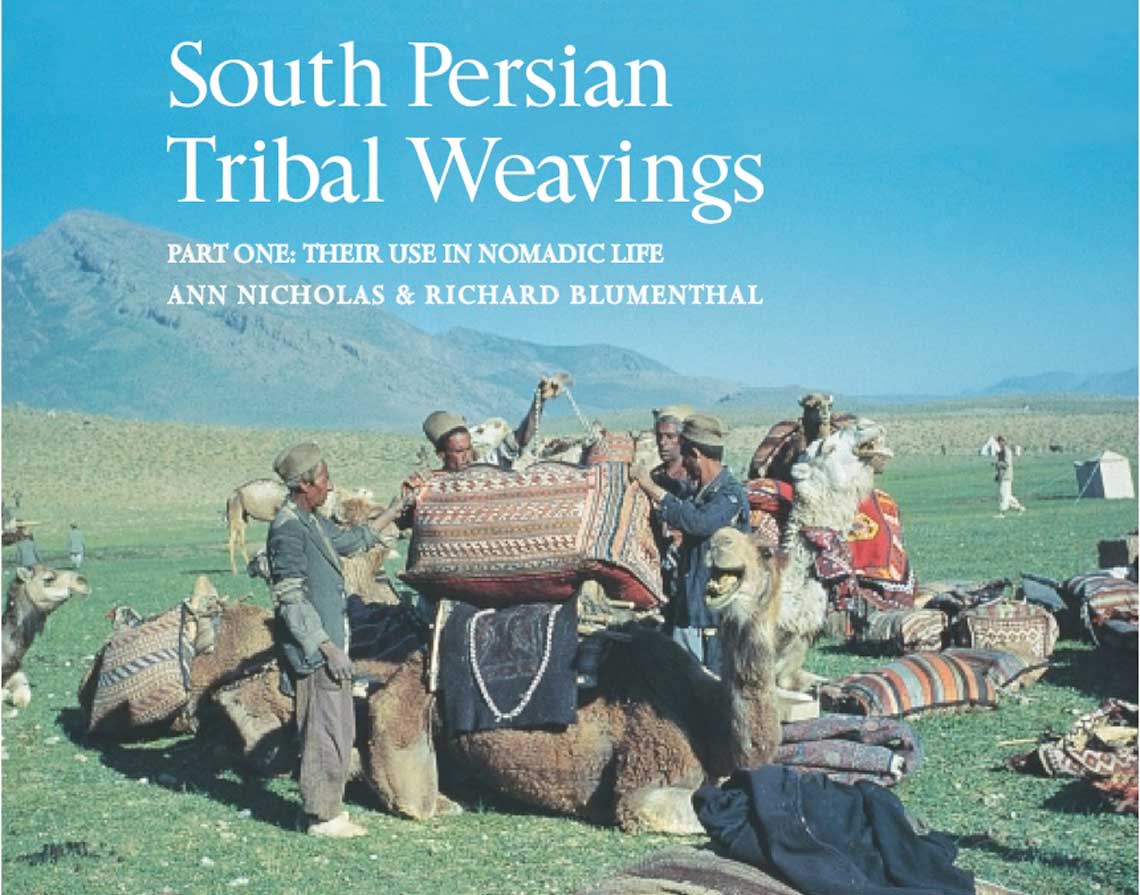

This group (bayleh)is led by a senior man, and several baylehtogether are led by a headman (kadkhoda), who helps plan the migration. Headmen meet to decide the starting date for each migrating group and a schedule for the campsites. Before starting, there is much work to be done. Tents are taken down and packed away and, with agricultural equipment and animal feed, stored at a village near the pasture. Looms and cooking equipment are disassembled. Each family’s food and household posses sions are packed in woven bags. After everything is packed, the bags are sorted and loaded on the pack animals, mostly mules and donkeys. In Baroness Ullens’ 1951 photograph of bags packed for the Qashqa’i migration, a large boxlike bag, a mafrash or khabgah, is being loaded onto the camel (11). Various other single and double flatwoven bags are scattered on the ground. The Qashqa’i also use camels as pack animals, while the Bakhtiari and Lurs use cows or oxen. These animals carry the heaviest loads, and large sturdy single bags are woven for them. These may be longer than wide or vice versa. The longer ones (joval)are often used in pairs for the transportation and storage of grain. David Duncan’s 1946 photograph shows a camel being loaded with such a joval (66) and an example from the Cook Family Collection is also shown (88). The wider large single bags (galeh)are often sewn up the middle to form two separate pouches. During migration, they may be balanced on the animals with the mouth left open for easy access to the contents. At other times they are used for storage, as in Daniel Bradburd’s 1975 image of a galeh full of potatoes (99). Summer and winter pastures can be several hundred miles apart.

Loading a large single bag (joval) during the 1946 Qashqa’i spring migration. Photograph by David Douglas Duncan, ‘Photography Collection’, Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin

Qashqa’i passing through oak groves on the spring migration, with colorful utilitarian bags displayed on the pack animals. Photograph by Jennifer Scarce, ca. 1970, after Jenny Housego, Tribal Rugs, London 1978

Potatoes stored in a largesingle bag (galeh) sewn down the middle, woven by the Komachi, Kerman area nomads who only made flatweaves. Photograph ca. 1975 by Daniel Bradburd

Travelling ten to fifteen miles a day, the migration lasts a month or more. Most social interactions outside the migration group occur during the migration. Nomadic families present their best face for the migration. Women wear their finest clothes and their most colorful weavings are displayed on the outside of the pack animals. Many photographs of the migration such as Jennifer Scarce’s circa 1970 image show nice weavings on the animals (77), while others show camels loaded with pile rugs. In Ullens’ 1952 photograph of a Khamseh family, a chanteh is shown hanging on a donkey (1100). We have seen many photographs of chanteh on pack animals, usually in the tall narrow format for holding water pipes or spindles (55) but occasionally in a squarer format (33)). The nomads are not self-sufficient. During the migration they must stop at a bazaar to buy supplies and trade woven goods. They buy

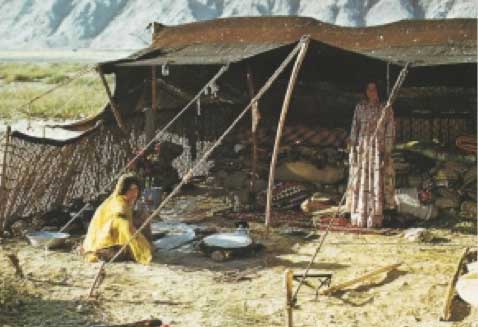

food, such as wheat, rice, salt, tea, and sugar, along with cloth for clothing, which they no longer weave. Although women do the weaving, it is the men who trade or sell the pieces in the bazaar. While living in the pastures, they care for their flocks, weave, and make yogurt, butter, cheese, and cooking oil from milk. Each family has a plot of land in both pastures, on average about a hundred acres, where the flocks graze and some crops are grown. In the winter they must protect their flocks from the cold and rain, especially the newborn lambs and kids. In the summer it is dry and warm, and the herd is sheared and culled. Excess animals, wool, and some milk products are sold at mountain markets. The nomads live in rectangular black goat-hair tents which are loosely woven to provide ventilation, but when it rains the goat-hair swells, making the tent waterproof. The tent is made of long narrow strips of plainwoven cloth, which are sewed or pinned together to form the tent. Size varies according to family size and status. If a family needs a larger tent, new strips are woven and added on. Three tents are used: a heavy winter tent that is enclosed on all four sides; a lighter three-sided summer tent; and a small light tarpaulin for shelter during the migration. In the back of the tent is a storage unit.

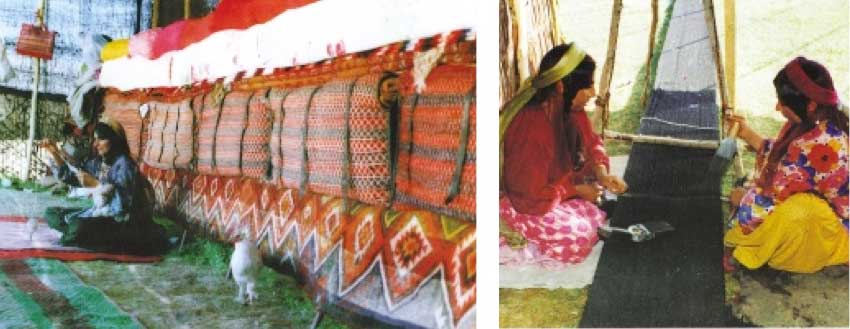

The same bags used during the migration are used to store food and household possessions. Inside these bags smaller containers may be hidden which hold important items such as medicinal herbs, dyes, and jewellery. The storage unit is made by stacking rocks several layers high, after which bags are piled on the rocks, and covered with a long colorful flatweave, such as a gelimor jajim. The rugs (gabbeh), flatweaves and other materials used for sleeping are stored on top. A 1970s photograph by Antony Hutt shows a pile of bags inside the summer tent before being covered (1144). Inside the tent, chanteh holding special items such as spoons, spindles, or pipes (1133) or important papers hang on the tent poles. A salt bag (namakdan)may also hang in the tent. Salt, spices, rice, and seeds for planting are rolled into small cloth bundles, tied, and stored in the namakdan. A small tin chest, the only box owned by most families, holds tea and tea-making equipment. Piled carpets or felt pads (namad)lie on the floor. A circa 1975 photograph by Kiani of the inside of a Qashqa’i black tent (1177), shows how the colorful patterns of the chanteh, piled carpets, and other weavings provide decoration. Wool from the flocks is spun using a drop-spindle, and is a constant activity for all, from young girls to the oldest women. Weaving is done at both the summer and winter pastures. A horizontal ground loom, which is easy to set up, take down and load onto a pack animal, is used to make coarse utilitarian cloth, flatwoven and knotted pile weavings (1155, 1166).

Khamseh family on migration, Fars, 1952. A small flatwoven bag (chanteh) hangs on the donkey. Photograph by Maria Ullens,Baroness Ullens Archive, Fine Arts Library, Harvard College

Qashqa’i pile saddlebag face, ca. 1880. The eight-pointed star within the octagon is a very early Turkic motif. Note the mixed pile and flatweave closures. 0.53 x 0.56m (1’9″ x 1’10”). Authors’ collection

Qashqa’i saddlebag in warpfaced alternating float-weave with two-color patterning, late 19th century. This structure is primarily woven by the Qashqa’i and used for bags, trappings, and horse blankets. 0.33 x 0.71mm (1’1″ x 2’4″). Authors’ collection

Women weave throughout their lives. Weaving is a social, co-operative activity, especially when making pile rugs, coarse cloth, and tent strips, as seen in Dr Kiani’s 1975 photograph of women weaving black goat-hair tent cloth (1188). Several types of gelim-like small flatwoven cloths (sofreh)are made for use with food. A dining sofreh is used as a ground cloth on special occasions where food is served and eaten. Two other types are for daily bread-making: a flour sofreh to hold the starter dough and flour, and a bread sofreh to store the loaves after baking.

Afshar sumakh spindle bag, late 19th century. Woven as one square piece, it is folded in half and stitched to form the small bag. 20 x 29cm (8″ x 11 1 ⁄ 2 “). Authors’ collection

Khamseh Confederation pile saddlebag face, ca. 1880. Elegant and superbly woven, this finely knotted (ca. 2,976 /dm 2 = 192/in 2 ) bag face has soft lustrous wool and a cloth-like handle. The design is attributed to the Basseri tribe. 0.61 x 0.55m (2’0″ x 1’9 1 ⁄ 2 “). Authors’ collection

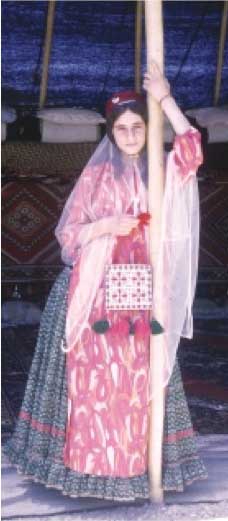

The women mostly weave utilitarian items, but at times a knotted-pile piece is woven for trade. A special piece may be made to celebrate an important occasion, for instance a hammock cradle (nanu)for a new baby, or a fine piece as a gift for a special person (2233). For their own use women weave small, dainty chanteh, which hold jewellery, a mirror, money, and other personal items (2211). Usually stored away, they are worn only on special occasions, as seen in a 1952 photograph by Maria Ullens of a young Qashqa’i woman (44). Exquisite small bags are also woven for special purposes such as storing a man’s pipe (chopoq) and/or tobacco (1199).

Weddings are traditionally held in late summer. Marriages are usually arranged within the tribes between people from different migrating groups. When a marriage is agreed, one of the literate men in the group writes the marriage contract. A girl learns to weave from the older women in her family, and by seven or eight she is a good weaver and begins to make a dowry. Almost all dowry items are utilitarian: bags, various flatwoven cloths, and other household items. Other special weavings, for instance a ceremonial horse blanket for the bridal procession, or fine pieces as gifts to the groom and his family (2222), are sometimes included in the dowry. The wedding celebration is held at the groom’s family pasture. On the day, the young bride bids goodbye to her natal family (many women seldom see them again). Then the dowry items are loaded onto the pack animals and, with two distant relatives, she rides in procession to her wedding celebration. In Dr Kiani’s photograph of a Qashqa’i bridal procession, the horses are adorned with tasselled blankets (2200). For the celebration a special bridal tent is made with flatweaves, often gelim from the storage piles of the groom’s relatives. Dowry items and wedding gifts are stacked in the back of the bridal tent. The wedding celebration lasts several days with feasting, dancing, and games.

Qashqa’i threesided summer tent showing a pile of bags packed with household possessions before being covered with a gelim. Photograph by Antony Hutt, ca. 1970, after Housego 1978

Qashqa’i flatwoven saddlebag face, ca. 1880. The very finely woven field in reverse offset sumakh represents the pinnacle of Qashqa’i weaving. 0.53 x 0.56m (1’9″ x 1’10”). Authors’ collection

Qashqa’i woman spinning, ca. 1975. The hanging chanteh, the rugs, and the storage unit cover provide color and decoration inside the black tent. Photograph by Dr M. Kiani, from Departing for the Anemone: Art in the Gashgai Tribe, Shiraz 1992

Qashqa’i women weave a black goat hair cloth tent strip on a ground loom, ca. 1975. Photograph by Dr M. Kiani, from Kiani 1992

Weddings are an important rite in south Persian nomadic culture, and the dowry, the ceremonial horse blanket, the gifts, and the bridal tent all show the importance of weaving in this culture. Most of a south Persian nomad woman’s status and prestige is defined by her weaving skills; such weavings are proudly displayed within the family’s tent. A talented and accomplished weaver is respected and admired by both men and women in her tribal group. But weaving gives more than just status to a woman; it is her contribution to family income and her principal opportunity for any artistic expression. A variety of functional weavings are indispensable in south Persian nomadic life. They provide shelter and storage for the tribe’s possessions, and color and beauty the year round. They present a measure of a family’s wealth and status and are a vital part of their livelihood. Each one has many uses. Bags used for transport on migration become storage containers in the tent.

Afshar sumakh tobacco bag (back), 19th century. With archaic designs and jewellike colors, the flap folds over to close the pouch. 27 x 16cm (10 1 ⁄ 2 ” x 6 1 ⁄ 2 “). Authors’ collection

Qashqa’i bride wearing a long white head-cover rides in procession on a white horse, ca. 1975. The tasselled ceremonial animal blanket is often woven as part of the dowry. Photograph by Dr M. Kiani, from Kiani 1992

Qashqa’i chanteh, late 19th century. This finely woven small single bag with a stunning zigzag design on back has the same structure as the saddlebag (12). The closure is simple and elegant. 23 x 19cm (9″ x 7 1 ⁄ 2 “). Authors’ collection

Khamseh Confederation pile saddle rug, ca. 1880. The directional design has a prayer niche (mihrab) form. The rug has a cloth-like handle and beautiful warm colors. Note the unusual 2.5cm (1″) wide plainwoven selvedges. 8 0.79m x 0.65m (2’7” x 2’ 1.5″). Authors’ collection

Qashqa’i pile saddlebag face, ca. 1890. The design is a remarkable synthesis of south Persian tribal, workshop, and classical Persian carpet traditions. Tightly woven (ca. 2,820 knots/dm 2 = 182/in 2 ) with depressed warps and a firm handle. 0.58 x 0.64m (1’11” x 2’1″). Authors’ collection

Large single bags, which hold grain on the migration, may also be used to carry goatskins filled with water for the tent. Chanteh hold important personal items, both in the tent and on the road. The gelim or jajim that cover the storage unit are also used as blankets and in forming the bridal tent. Pile rugs serve as ground covers inside the tent, while outside they become meeting places where men sit, drink tea, and smoke. Weavings are used as gifts on important occasions. Over the years we have seen at least 5,000 photographs of south Persian nomadic life. How different would they have been had they been taken earlier, say in the second half of the 19th century? We have discussed this with an ethnographer, 6 and believe that they would probably have been little different to the ones we have seen. Nomadic life changed little until the 1960s, when the government began grading roads in southern Iran, some on the migration routes. Then life changed rapidly: horses were replaced by motorcycles, pack animals by jeeps and trucks, and goatskin bags by plastic water jugs. Many families ceased migrating and settled in villages. But one puzzle remains: we have never seen a piled saddlebag in any of the thousands of photographs we have examined. Not on the animals during the migration, not displayed in the tent, and not in photographs of the wedding celebration. Arguably piled saddlebags and saddlebag faces are the woven objects Westerners most associate with South Persian nomadic life. Why are they not present in the photographs? In the next issue of HALI we will explore the economic, political, and social conditions in 19th century Iran to try and cast some light on this surprising observation.