Art & Antiques, September 2014

Art & Antiques, September 2014

Twentieth-century carpets weave strands of modernist geometry and color abstraction into traditional formats, taking textile into the realm of fine art.

From Sweden comes a large, intricate flat-weave carpet with the bordered rectangles-within-rectangles type of design familiar from oriental examples. Except this one’s color scheme is like nothing ever seen in Samarkand or Bokhara—all various shades of purple. Amid the diagonal stripes and diamonds, instead of the traditional regular lozenges it has little de-centered blobs, like amoebas doing their own thing. A French pile carpet, bursting with bright reds like poppy blossoms, set off by pale greens and dark brown splotches, seems more like an abstract painting than a textile. And from England comes a square, handwoven wool carpet whose design of vines, flowers, and bulbs recalls a medieval tapestry. These three carpets, by Marianne Richter, René Crevel, and C.F.A. Voysey, respectively, came on the block this past June at Wright, a Chicago auction house that specializes in 20th-century design, and they represent the aesthetic diversity and boldness of modernist carpets, a genre that has long been recognized by designers but is increasingly finding favor among collectors as works of art.

The sale, Wright’s first dedicated solely to carpets, made $1,038,060 in 72 lots, testifying to an untapped enthusiasm for 20th-century pieces. Sale expert Michael Jefferson says, “I found there was a real void in terms of market attention on carpets in general. Christie’s and Sotheby’s in New York had done them, mainly with oriental rugs. But we thought, let’s do something totally different, shift people’s thinking.” Wright started offering what Jefferson calls “Moroccan carpets that are contemporary incarnations of nomadic tribal carpets” and then went on to “prop them up with things that are outside the tradition, start to break out of that box of conventional wisdom.”

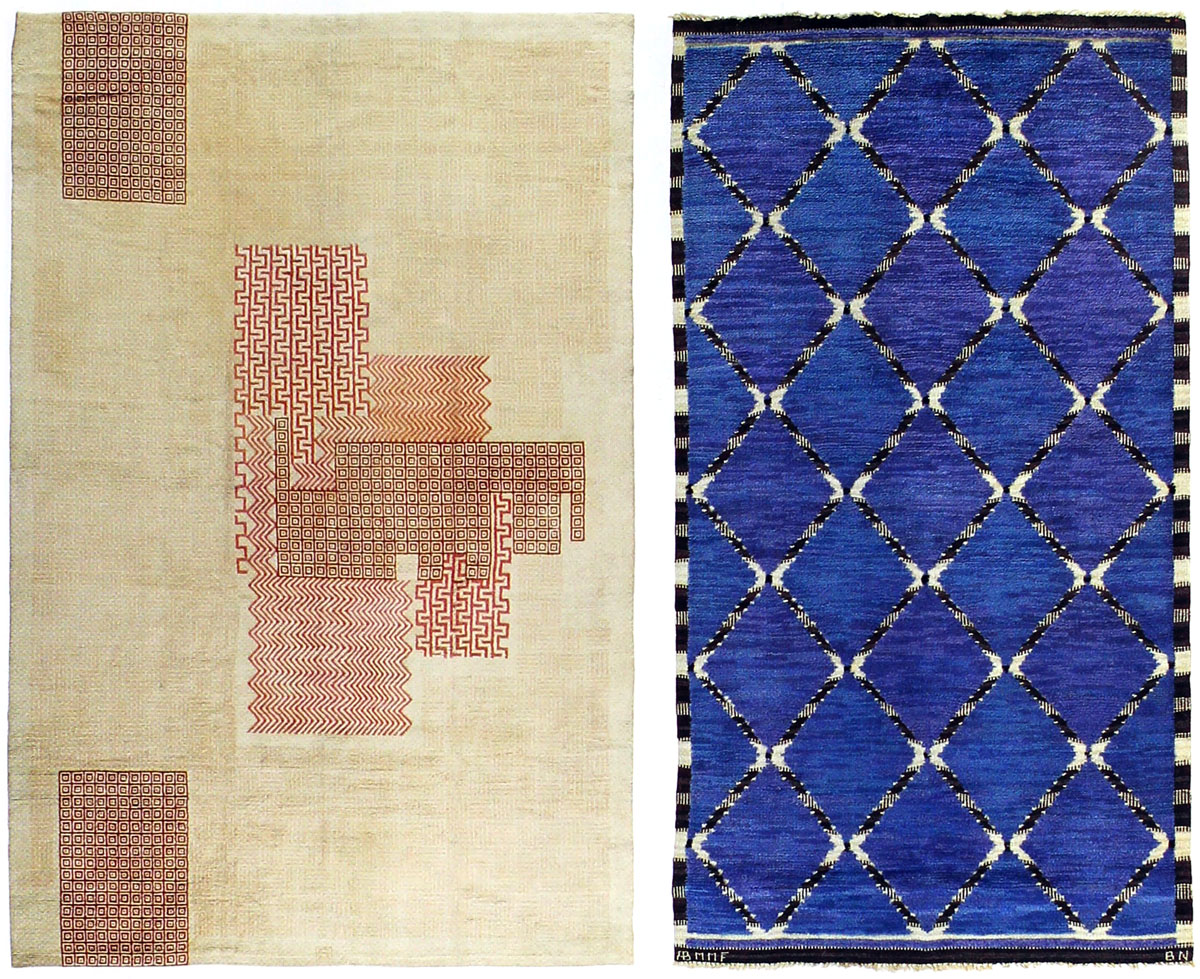

From left: C.F.A. Voysey, Donnemara carpet, first quarter 20th century, hand-woven wool; Barbro Nilsson, Falurutan flatweave carpet, 1952, hand-woven wool.

Among the most prominent pieces “outside the tradition” are Swedish carpets, such as the purple Richter. Not that Scandinavia doesn’t have a tradition of rug-making. In the Middle Ages, textiles from the Near East and Central Asia reached Northern Europe, and Nordic weavers adapted the techniques to their harshly cold climate, creating very deep-piled shaggy rugs called ryas that kept kings and commoners alike warm during the long, dark winters. In time, these textiles fell out of fashion with the elite and were consigned to the dubious realm of folk craft, where they remained until the early 20th century, when design pioneers like Marta Maas-Fjetterstrom were inspired to do something completely new with them.

From 1919 until her death in 1941, Maas-Fjetterstrom operated MMF, a firm that still exists, designing her own rugs and inviting artist/designers such as Richter, Barbro Nilsson, and Ann-Mari Forsberg to join her and carry on the work. “I find no more inventive and creative work than the MMF studio,” says Jefferson. “Maas-Fjetterstrom did her own design and her own weaving and then passed it on to other people. You see this great opening up of creativity. All of them are women artisans.”

From left: C.F.A. Voysey carpet, first quarter 20th century, hand-woven wool; Marta Maas-Fjetterstrom, Dukater flatweave runner, 1924, hand-woven wool.

Influenced by austere theorists such as Le Corbusier and Josef Albers, the MMF artisans managed to hew to strict modernist design principles and rigorous standards of hand work while still imbuing their carpets with rich and even exuberant colors and patterns. Most of them appear somehow ancient and modern at the same time, and this visual-cultural tension gives them power and flexibility of application. “From a style standpoint,” says Jefferson, “they lend themselves to a range of decors and interiors and are very rich and vibrant to the eye. But they don’t give offense in an austere, minimalist environment, and they also relate to ornate interiors, for example, chinoiserie.” At the Wright sale, a red-dominated Falurutan flat-weave carpet made by Nilsson in 1952 brought $112,500 against an estimate of $50,000–70,000, while a Bla Plump flat-weave by Maas-Fjetterstrom herself went for $35,000 against an estimate of $20,000–30,000.

French Art Deco carpets represent another major area of creativity and demand in the 20th-century carpet market. “The Deco market has been robust for decades,” explains Jefferson. “It’s been sustained by a broad interest in the various things that surround it, by the great art that circles around it. The furniture of E.J. Ruhlmann and Eileen Gray is as strong as it’s ever been.” The great Ruhlmann himself was also a carpet designer. Those who collect Deco carpets tend to have cohesive Deco interiors whose floors virtually cry out for such coverings, which are rare and tend to be expensive. The Franco-Brazilian designer Ivan da Silva Bruhns is a special favorite. A pile carpet of his, with textured herringbone-like elements in various reds woven at uneven intervals into an airy, open background of light tan, recalls Synthetic Cubism. At Wright it sold for $93,700 (est. $50,000–70,000).

From left: Ivan da Silva Bruhns, pile carpet, second quarter 20th century, hand-woven wool; Barbro Nilsson, Snedrutan half-pile carpet.

While there are many other schools and types of modernist carpets, the third main division of the genre, and the earliest in terms of time, is English Arts & Crafts. Kicking off the 20th century, this movement, spearheaded by William Morris and inspired equally by medieval traditions and modern socialism, sought to bring hand-crafted excellence to the masses. While it failed to keep costs down far enough to make its products affordable, it did succeed in creating beautiful and impressive works that meld modern and archaic elements, but in a very different way than MMF. Charles Francis Annesley Voysey, originally an architect, was the premier carpet-maker among the Arts & Crafts adherents. He favored plant and animal forms and a flowing, organic style, and created his patterns separately from his borders so that the designs could be fabricated in a variety of sizes. A hand-woven Donnemara carpet by Voysey brought $30,480 at Wright’s June sale.

Twentieth-century carpets are also being championed by a small selection of dealers, notable Doris Leslie Blau in New York, whose owner, Nader Bolour, comes from a long line of Iranian rug experts and curated Wright’s recent sale. Another gallery with Persian roots, the Nazmiyal Collection, also in New York, has discovered the genius of modern Scandinavian carpet design and now has a strong sub-specialty in the area. And Swedish modernist carpets can often be found at the prominent Stockholm auction house Bukowksis, in the land of their origin.

By