This article originally appeared in the October 2013 issue of Architectural Digest

Château du Grand-Lucé, interior designer Timothy Corrigan’s palatial estate in France’s Loire Valley, comes with a lovely legend. In 1781 the surrounding village, built mostly of wood, was destroyed by a fire that started in a bakery. The chatelaine, Louise Pineau de Viennay—a daughter of the residence’s original owner, Jacques Pineau de Viennay, Baron de Lucé, a state councillor under Louis XV—supposedly sheltered the townspeople in her splendid outbuildings while she had their homes and shops reconstructed in tuffeau, the region’s creamy white limestone. Eight years later, when the revolution came, not only was the lady of the house spared (her generosity surely remembered) but so were Grand-Lucé and its treasures, among them a room full of rare chinoiserie murals.

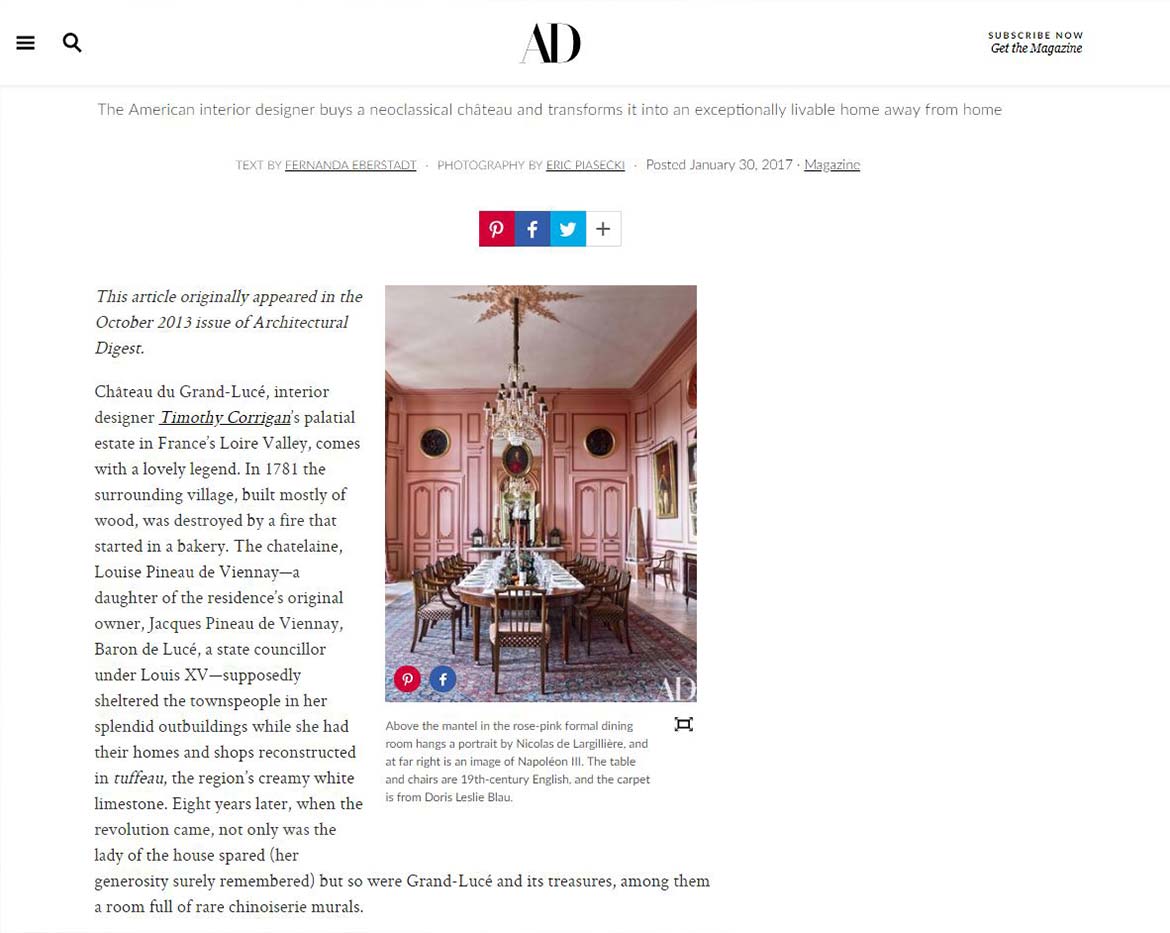

By 2003, when the Los Angeles–based Corrigan discovered that the 45,000-square-foot property was being sold by the French government, the building’s neoclassical glories had been dimmed by centuries of paint and decades of benign neglect. Built between 1760 and 1764 by engineer Mathieu de Bayeux, the château had barely been modernized. A private home until the mid-20th century, it was transformed into a military hospital during World War II and eventually pressed into service as a tuberculosis sanatorium—neither of which did much for its condition, as Corrigan’s new book, An Invitation to Château du Grand-Lucé (Rizzoli), explains. “There was no heat and little electricity,” recalls the designer, who left a successful career in advertising in 1997 to follow his passion for decorating. Still, stumbling across Grand-Lucé was a coup de foudre. “It had such a luminous feeling,” says the Francophile, who previously restored two venerable country residences in this part of the world, one in Normandy, the other near Angers. “You could tell it just needed to be brought back to life.”

Resurrecting the estate, which is entered via a monumental gate facing the village of Le Grand-Lucé’s main square, was certainly daunting. Though the government gladly sold the property to Corrigan in 2004—a feature on Grand-Lucé’s initial renovation appeared in AD’s September 2009 issue—the transfer came with a double-edged honor. The château is a historical monument, meaning that every shade of paint the designer planned to use had to be vetted by Les Architectes des Bâtiments de France, fearsome watchdog of the nation’s patrimony.

Luckily Corrigan’s furnishings were of minor interest to those officials, so he has cheerfully ornamented a marble bust in the entrance hall with a turquoise necklace and accessorized a mantel in a bedroom with Day of the Dead figures from Mexico. “I didn’t want the place to take itself too seriously,” the designer says. “We’re not in a museum. The message is, we’re just having fun.”

Typically Corrigan spends a total of two months each year living at Grand-Lucé. It’s a soul-reviving vacation home that blends Age of Enlightenment elegance and Southern California informality. To loosen up the Grand Salon’s fluted pilasters and carved overdoors, Corrigan brought in big, comfortable sofas covered in an off-white damask and scattered with tapestry pillows. Their presence makes what could be a traditionally starchy sitting room into something the gregarious designer calls “a major hangout zone” for houseguests. He wishes he could take credit for the room’s outstanding structural feature: an interior window that Bayeux installed above the mantel and which offers a glimpse into the neighboring Salon Chinois. The name of the latter space comes from the room’s radiant 18th-century murals, painted by Jean-Baptiste Pillement, depicting green-eyed Asian damsels playing with parrots while their menfolk fish from a stone basin.

In bringing the château in line with contemporary notions of comfort, Corrigan converted a boudoir into a modern kitchen—thus creating a marvelous cooking space that boasts a parquet de Versailles floor. He also persuaded French authorities to let him remake a fountain at the heart of the walled rose garden into a small, round swimming pool.

Like any big house, Grand-Lucé is at its best when filled with people, and Corrigan enjoys hosting impressive gatherings. The two top floors are devoted to guest rooms—14 have been renovated, each with its own luxurious en-suite bath, while the remaining four still contain notices from sanatorium days, informing patients of the hours and prices of their meals.

On the château’s south side, towering French doors open to an 80-acre paradise. Straying beyond the picturesque outbuildings— among them a chapel and an orangerie—guests find themselves in formal gardens (restored by the French government in the late 1990s and open to the public on a limited basis) that meld into meadows, woodlands, and a lake. Vegetable plots are laid out in mischievous curlicues, and stone goddesses that were long-ago presents from Louis XV frolic in clearings where for centuries the resident seigneurs hunted stags. Given all this, it’s no wonder visitors find themselves echoing Corrigan’s reaction when he and Grand-Lucé were first introduced: “Oh my God, I can’t believe someone could actually own all this.”

The Grand Salon overlooks the château’s gardens, which were restored by the French government and are open to the public six times a year; fluted pilasters frame the doors and windows, and the George Smith armchairs are upholstered in a Schumacher linen.

Clad in a Schumacher damask, a Knole sofa anchors a sitting area in the salon; the table lamps on either end are repurposed 19th-century gilt-wood colonnettes, the cocktail tables are vintage Jansen, and the throw on the armchair is by Hermès.

This article originally appeared in the October 2013 issue of Architectural Digest