PETER DAVIES & MUAMMER SAK Kilims have been collected and studied in the West for less than fifty years, with a focus on highly decorative antique pieces. More recently we have begun to consider the large body of utilitarian weavings also performed important functions in the rural Anatolian household.

The authors have studied one Central Anatolian tradition where the weaving of drop cloths is intimately related to the importance of bread and bread-making within the community.

hat drop cloths have always played a significant role in rural Anatolian life is clear when these homely items are seen in the context of the typical nomad tent or cottage, where practically all household activities take place on the floor, or on the ground of an outdoor courtyard, or on a flat roof top. In a household with virtually no furnishings, almost all life activities, including the kitchen tasks of cooking, baking, food processing, dish-washing, and so on, require the creation of a clean working surface. In Cappadocia one group of drop cloths, known as itea (also iteÌi and ita), is associated with bread-making and other wheat-processing activities. The term does not appear to be of Turkish origin, and is used not only by weaving populations in Cappadocia but also by villagers and nomads in certain areas of the Taurus Mountains, as well as in the NiÌde area. How much more widespread its use is throughout Anatolia remains to be established. In the rug world, both within and outside Turkey, the itea has tended to be given the misnomer sofreh, a word of Persian origin. In rug shop terminology, any weavings associated with food preparation and consumption (particularly those with zigzag borders) have been casually identified as sofreh. However, the term does not appear to have been in general use in Turkey until its recent importation. True, there are similar native Turkish terms such as sofra, which has, however, customarily designated a low, square, wooden eating table, and by extension the meal set upon it. A related term, sofra bezi, has been restricted to the cloth placed under an eating tray to catch crumbs and food. Itea is a more accurate term for the weavings the Cappadocians traditionally used in making bread and processing other wheat-based foods. In appearance the Cappadocian itea is utilitarian rather than decorative in the usual sense.

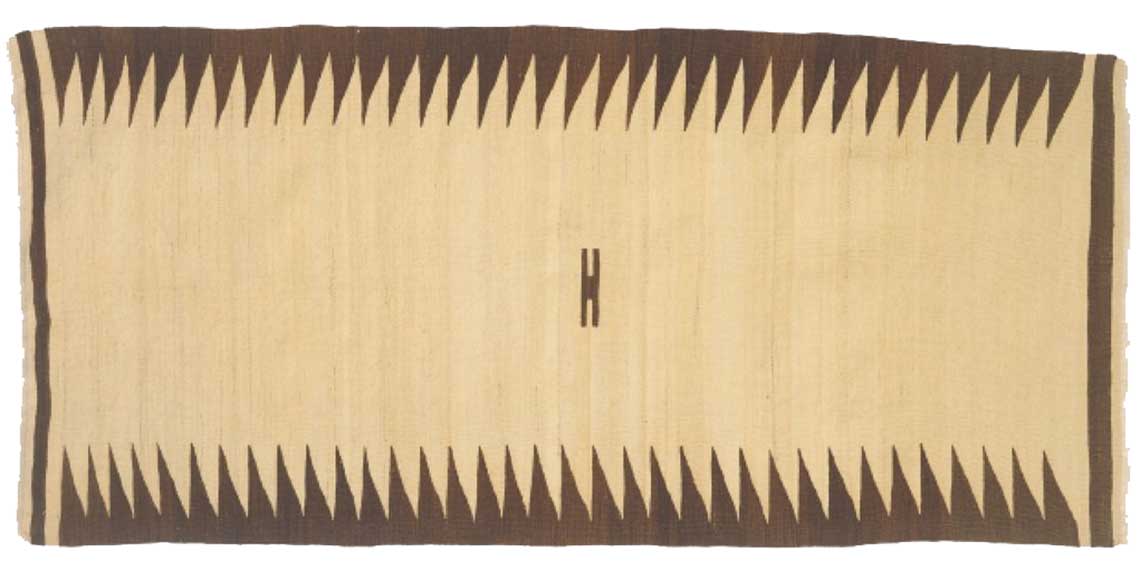

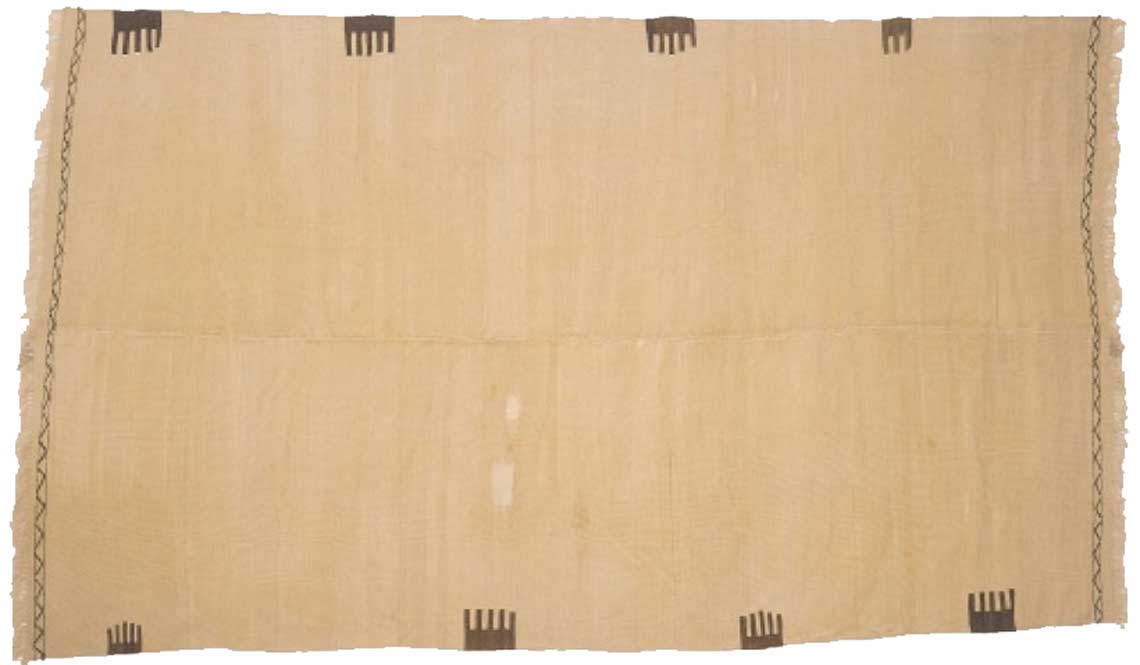

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 0.86 x 1.88m (2’10” x 6’2″). Courtesy Turkana, New York

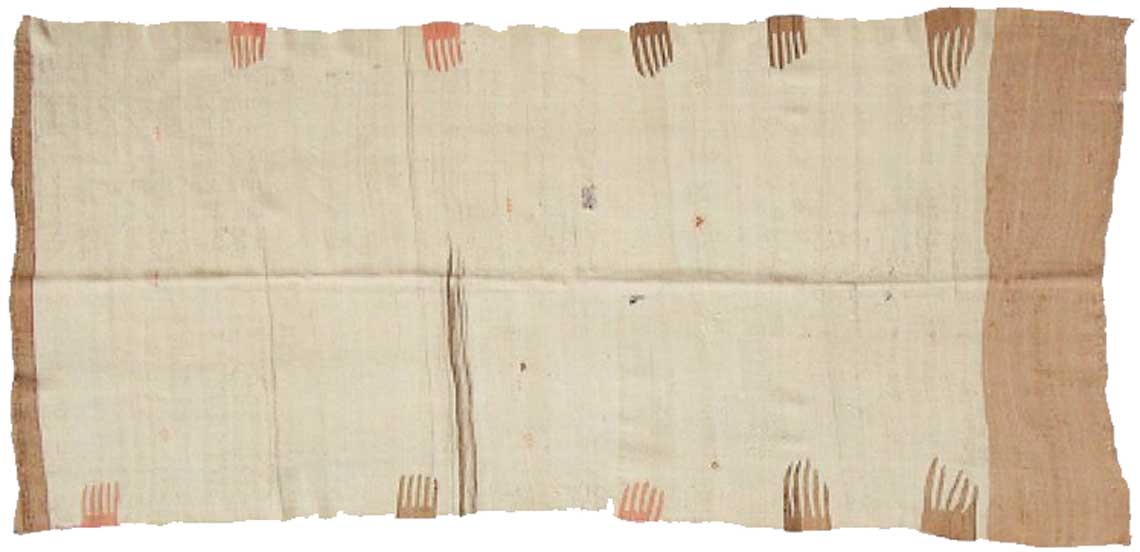

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.78 x 2.49m (5’10” x 8’2″), woven in two parts and joined. Courtesy Turkana, New York

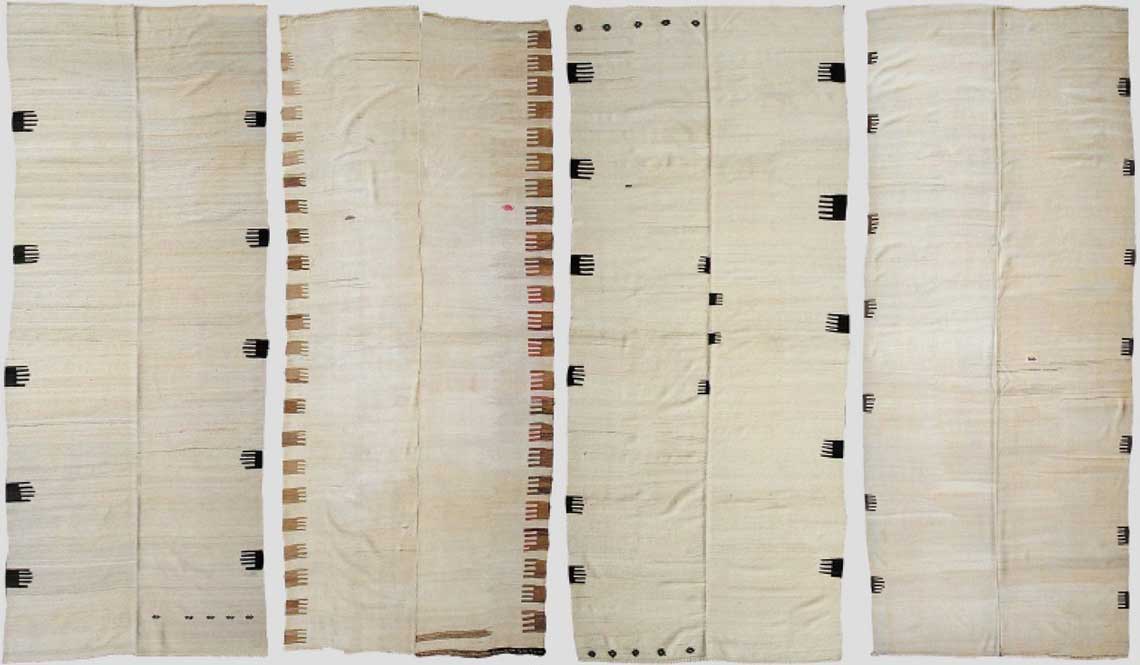

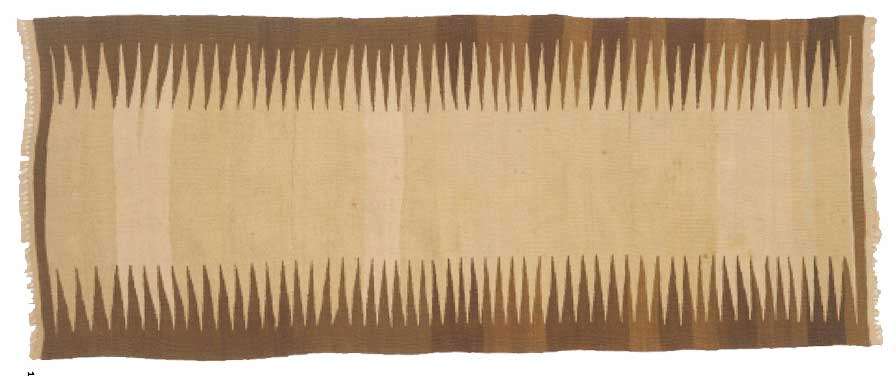

They come in a number of different sizes, shapes and thicknesses, and are decorated in several different ways. One variety is characteristically large, measuring approximately six foot in width by ten foot in length, and often woven in two pieces (3, 6, 8, 9, 10). There are two basic types of large-format itea: one is woven of a thick ply of wool which produces a heavy weave, with approximately 20 wefts and 8 warps per inch (3, 9). The other more finely woven version has a thinner ply and tighter weave, with approximately 50-60 wefts and 10 warps per inch (8). Another variety of itea is small and narrow (1, 11, 12) averaging around two feet in width and approximately six feet in length. While there are differences in size and weave in the various categories of itea, the bulk of them are woven of undyed ivory and brown yarns, and are minimally decorated. The larger pieces tend to have hand- or finger-like forms spaced along the selvedges, while the smaller, narrow pieces are usually edged with zigzag motifs. The decorated edges are generally woven in dark brown yarns. Thus the typical itea palette is a simple ivory and brown, although there are some examples with yellow or black/brown fields. The typical itea is woven in a simple weft-faced or tapestry technique,

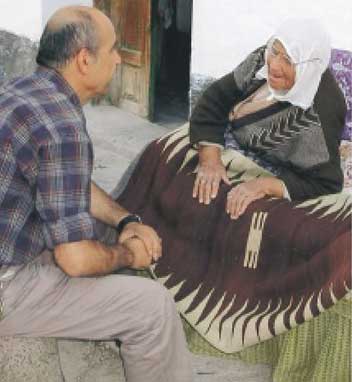

rather than the more complicated and time consuming slit-weave tapestry more typical of Anatolian kilims. Turks would designate the itea as being in the sade mode, that is plain, unadorned, simple. With their large ivory fields edged with minimal finger-like motifs or zigzag edgings, itea are striking for the simplicity of their designs and palettes. The expanse of negative space between the minimal ornamentation of the edges reveals the beauty of the materials and workmanship, rather than serving as a canvas for an elaborate design. In contrast, other kilims, such as prayer and main kilims, are ordinarily classified by Turks as in the ciddi mode, that is, covered with ornament, or in the canlı mode, alive with exuberant color. Any attempt to reconstruct what the itea is and how it functioned in village life is hampered by the usual problem in studying Anatolian weaving traditions: the attempted study has come too late. The weaving of itea and their general use in cottages and tents ceased long ago. Even memories of the itea barely survive in the minds of a tiny elderly population. We interviewed a number of elderly residents of Ürgüp, Nar, and Uçhisar, most of them now in their eighties, who remember that the weaving of itea stopped about seventy years ago. The humble, utilitarian role of the itea is suggested by wedding customs still remembered in Cappadocia. Older people recall that the itea was not regarded as a standard part of dowry preparation and, indeed, was not considered a suitable wedding present. It would have been considered comparable to our giving a mop and bucket for the occasion. An itea, some old women remember, would only have been a suitable wedding present in the case of a very poor bride and groom. Those elderly survivors interviewed (10) also remembered a period when the wool itea were replaced for a time by cotton cloths, but they do not recall why the weaving of woolen panels stopped. It’s possible that the shift occurred because of a reduction in local sheep flocks or, more likely, due to the availability of, mass-produced cotton cloth. So using plain cotton panels probably became standard practice because it saved time and labour. While we would prefer to think of such rural cultures as being devoted to the continuity of tradition, the truth is that given the intense demands on the female members of the household – food processing and preparation, child care, wool preparation and weaving, as well as other household and agricultural responsibilities – any innovation that reduces labour has always been rapidly adopted by rural cultures. And with the adoption of new methods or sources, ancient practices quickly vanish from communal memory. Significantly, the time at which the villagers of Cappadocia shifted from wool to cotton cloths roughly coincided with the wholesale shift in Anatolian villages and tents from copper trays, bowls, and ewers to plastic ones, and from camels as cargo conveyors to trucks. Ultimately even the cotton version of the itea fell into disuse as bread-making and noodle and bulgur processing were taken over commercially and ceased being domestic tasks. Today in Cappadocian villages, these wheat related tasks are carried on at home by only a tiny fraction of the population.

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.19 x 2.59m (3’11” x 8’6″). Courtesy Aksa Kilim, Ürgüp, Turkey

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.68 x 4.52m (5’6″ x 14’10”). Courtesy Aksa Kilim

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.86 x 3.78m (6’1″ x 12’5″), woven in two parts and joined. Courtesy Aksa Kilim

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.87 x 4.52m (6’2″ x 14’10”). Courtesy Aksa Kilim

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.96 x 4.17m (6’5″ x 13’8″), finely woven in two parts and then joined, 4 warps and 20-24 wefts per cm2. Courtesy Aksa Kilim

The home tandur and the village public ovens have been made virtually obsolete by commercial baking operations. Thus the descriptions that follow are of practices that have long ago fallen into disuse among most of the rural population in Cappadocia. At one time the women of local households produced stacks of yufka, the thin sheets of dough used in making a thin, wafer-like, bread that could be stored readily for future use. They also regularly baked ekmek, loaves of bread, and made noodles, eriÎte. And they processed and dried wheat to produce bölge, bulgur. All of these wheat related tasks were regular domestic chores and were usually carried out communally in a manner reminiscent of the way weaving groups gather together. Every few weeks, on a set day, the women of six or seven neighbouring households gathered their materials together, including their itea, and pooled their labour, to produce yufka and bread in large quantities. Similarly at set times, they communally prepared eriÎte and processed bölge. For the making of yufka, a particularly tough, dense dough is required. In order to reach this consistency the women kneaded the dough with their feet. For this purpose, a large itea was spread on the ground, and the dough was placed on the itea and trodden on until the right consistency was achieved. Next, the small itea was spread on the cottage or tent floor to create a clean space for the bread board, and to catch any excess flour that might drop to the floor. The dough was formed into small balls and rolled on the bread board into thin sheets that were stored for future use. For bread-making both large and small itea were required. Bread-making began with the hamur teknesi, the bread-making box, a long, shallow, container in which the flour, water, yeast and salt were mixed, kneaded, and then left to rise with a small, narrow itea spread over the hamur teknesi to aid in the rising process. Once the dough was ready, the itea was removed and the dough formed into loaves and either baked in the home tandur or carried to the village public oven. After baking, the bread was placed to cool on a large itea (2) which was spread out on the ground. Large itea were also used in the preparation of eriÎte, crude noodles formed of strips of sun-dried dough. This process, as with bread-making, began with kneading dough in the hamur teknesi, after which it was rolled flat and cut into strips. Large itea were then spread on the flat rooftops or in a sunny courtyard, and the noodle strips were spread out to be dried, then bagged and stored. Similarly the large iteas were spread on rooftops for processing bulgur. Once the wheat had been hulled and boiled, it was spread on a large itea, usually on a rooftop or in a courtyard, to be sun dried. Whether or not the light- and heavy-weight large itea served different functions remains unresolved. The reactions of the elderly women suggest that both types were used indiscriminately for any function. Whereas in at least one instance, as described by an elderly man, there was the suggestion that the lighter itea was used for drying noodles and bulgur, while the heavy one was used for cooling bread. Another possibility is that the finely woven itea were used in preparing yufka dough, since the treading process required might have mashed the dough into the threads of loosely woven itea.

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.83 x 3.10m (6′ x 10’2″), woven in two pieces which are then joined. Courtesy Turkana, New York

As to why white and brown was the standard palette of the itea, the elderly women and men interviewed had no answers. It does, however, seem evident that for such a utilitarian item, expending the labour required for dyeing yarns would have seemed unnecessary. However, there are plenty of examples of utilitarian weavings for other purposes that were woven with dyed yarns. Quite possibly because the itea was used exclusively for wheat processing, natural ivory yarns would have been the logical choice as the dominant material. The powdery white of flour would undoubtedly have quickly obscured polychrome designs. The elderly population interviewed could not recall that anything about the itea was invested with meaning. They had no notion as to why the zigzag edging was used on the long, narrow pieces. or what the evocative handor comb-like forms on the larger pieces signified. When pressed, some of the women speculated that the hands could, perhaps, represent the hands of the women making the dough, or more fancifully, the Hand of Fatima, and thus fertility. That both the hand- and comb-like motifs tend to have five appendages could be significant. However, the interpretations volunteered by those interviewed appear to be speculative, prompted by the questioning rather than remembrances of past meanings. If the itea had any meaning beyond its function, it seems to be by way of the sacred associations Anatolians have traditionally had for bread and other wheat products. Bread is truly the central food at a Turkish meal, and Anatolia is the great bread basket of Turkey. The sacred associations with bread are attested to by the great pains Turks have always taken to prevent flour from falling to the earth during bread-making, and the care taken in Turkish daily life to see that bread is not discarded or trodden upon. For instance, it is customary if a crust of bread is found upon the ground for an Anatolian to move it to a place where it will be eaten by birds and animals rather than trodden on. Thus while the itea was humble and homely and virtually bereft of ornament, it seems to have had, nevertheless, a kind of significance deriving from its association with the sacredness of bread, which we acknowledge in our expression: The staff of life.

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 0.67 x 1.34m (2’2″ x 4’5″). Courtesy Aksa Kilim

Itea, Cappadocia, central Anatolia, 20th century. 1.76 x 1.96m (2’6″ x 6’5″). Courtesy Turkana, New York